College Isn’t Enough: Why Universities Provide Incomplete Job Training

College doesn't provide all the job skills employees need. Find out why universities provide incomplete job training and how employers can bridge the gap.

Imagine you’re a new college student trying to pick a major. Maybe you love art history and oceanography, but your parents warned you that you’d never get a real job with those degrees, so instead you choose something sensible like business. Now picture a manager working with a fresh college graduate, frustrated because despite the new hire’s business degree from a well-regarded university, they still don’t know half of what they need in order to do their job effectively. Whose fault is it?

Neither, it’s just a crisis of misunderstanding.

History of universities as job training

Universities in the United States have been seen as training grounds for professionals since the mid-1800s. By the middle of the nineteenth century, American society was becoming restructured according to the concept of career. While some of these students were learning law, medicine, or the other technologies of the time, the main focus was often on the liberal arts, the classically inspired disciplines of grammar, logic and rhetoric deemed to be essential for effective participation in public life.

In the 1980s, budget and tax cuts changed the focus of higher education aid from grants to loans. The idea was that students were a burden who should be supported by their parents, not by the federal government. State funding followed suit, and state higher education funding on a per-student basis is even lower today than it was in 1980. Not only has federal and state funding dropped, but the cost of education has skyrocketed. Tuition at private colleges surged an average of 44% from 1993 to 2013. At public institutions it jumped 79% during the same period.

Employers’ attitude towards job training changed

Some of this change coincided with a huge shift in corporate restructuring. A surge in downsizing cut out middle layers of management, which flattened organizations and created broader spans of control. Dr. Amy C. Lewis, Professor of Management at the College of Business at Texas A&M San Antonio, explains why this societal change affected career growth and shifted leadership training away from hands-on roles.

“Imagine you have a manager with a span of control of only five direct reports, like a shift manager at McDonald’s. If you wanted to become that manager, it’s very easy to get that promotion, because you’re only going up a little step: it’s incremental. But when you flatten the organization so much that to get from being the line worker up to moving into management is a huge jump, there’s no easy way to get those skills on the job within the same organization, unless it’s very deliberate by the company.”

DR. AMY C. LEWIS, PROFESSOR OF MANAGEMENT AT THE COLLEGE OF BUSINESS AT TEXAS A&M SAN ANTONIO

In earlier generations, a high school graduate would get an entry level job as a stepping stone, expecting that their employer would provide a mentor, training, and the opportunity to work their way to the top. We don’t see this as much anymore. Why train someone to become a manager when you can just hire a newly minted MBA and hope they’ve learned the appropriate skills?

Who pays for job training?

Today a college degree is one of the most expensive investments most people will make in their life, and students, justifiably, expect that it will pay for itself. In the 2000s, President Obama simultaneously stated his intention to make college available to as many people as possible while extolling institutes of higher education to make sure their programs adequately prepared students for the job market. This started a trend in terms of expectations that it was the worker’s job to show up already knowing how to do whatever position they were hired for.

Dr. Yustina Saleh, VP Research & Value at Visier, has an extensive background in using data science to uncover insights about skills and education in the labor force. As Labor Market Information Director for the State of New Jersey, she created a tool to use real time jobs and unemployment data to index occupations when the great recession hit. At Burning Glass, an analytics software company that decodes the ever-changing labor market, she founded the analytics division and created many of their skills, occupation, and education taxonomies and products that powered a wide array of regional planning and education analytics products.

College degrees as gatekeepers

Yustina says that when there are too many potential applicants for an open role, employers will use a college degree as a requirement to narrow down the field of choices. While using a degree as a gatekeeper may make it easier for recruiters, it also winnows out equally skilled people who don’t have a degree. This also adds inequality: higher education access is not equally distributed.

Colleges and universities, especially prestigious private universities, favor students with a strong academic background. “Ivy league admissions structure is still based on grades, and if you have those grades, you have a lot of resources. The selection process is intrinsically biased even if diversity quotas are met on paper,” Yustina said.

While at Emsi Burning glass, Yustina was part of a study that found surprising paths between a field of study and a person’s eventual career path. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York found in 2018 that only 27% of college graduates work in a field related to their major. While the few top careers for each program type were usually linear (for example, those who studied IT frequently went into software) the majority of graduates’ outcomes were dispersed widely among many different careers.

Universities do provide value

If this is the case, why did 83% of survey respondents in a Pew Research study say they felt college had paid off for them? Yustina firmly believes that a liberal arts education can provide a foundation for excellent career growth. The broad exposure to new ideas and critical thinking skills that a college education provides create a solid base for problem-solving abilities. In some cases, a broader base of study with a wide variety of influences may be even more valuable than a technical degree. Technology becomes outdated, but soft skills and critical thinking does not.

Nevertheless, Yustina does think universities should be more deliberate about what they teach. “College is lagging behind more and more when it comes to training. Students are going into colleges and finding the training is too theoretical,” she said. “People who are the most satisfied with their degrees are those who study something and then work in the same field, such as engineers who studied engineering and doctors who studied medicine. The people who were the least satisfied were the liberal arts students. Because when you don’t specialize, you start from the beginning no matter what field you go into.”

Certifications and stackable credentials

Universities have begun to respond to students’ demands by offering more certifications. “It used to be if you wanted to get a job in finance, you’d work under somebody like a CPA and get the hours and then sit for the test because you’d have an employee sponsor. Well, they’ve loosened up some things so now students can do some of these tests before they’ve even graduated,” Amy says. “But that also means the company doesn’t have to train as much, and so they can get into this mindset of assuming graduates should be able to know everything from day one. That wasn’t the mindset in our parents’ generations.”

Yustina believes one solution is to offer stackable credentials as a way of building an a la carte menu of skills so that college graduates have more options and so that employers can make hiring decisions on the skills required rather than using a degree as a gatekeeper. Rather than having a degree in X, a graduate will have a list of stackable credentials less like a catalog of required classes and more like the skill trees familiar to anyone who has enjoyed the complex character building of modern video games.

“An institution that does this well is Western Governor University. Their philosophy is very flexible. You don’t have a one-size-fits all degree; it’s career-oriented and flexible in their choices,” Yustina says, adding that if she’s hiring a recent college graduate, she’ll ask them about research projects and what courses they took to get a feel for their skill sets.

Which skills does your organization need?

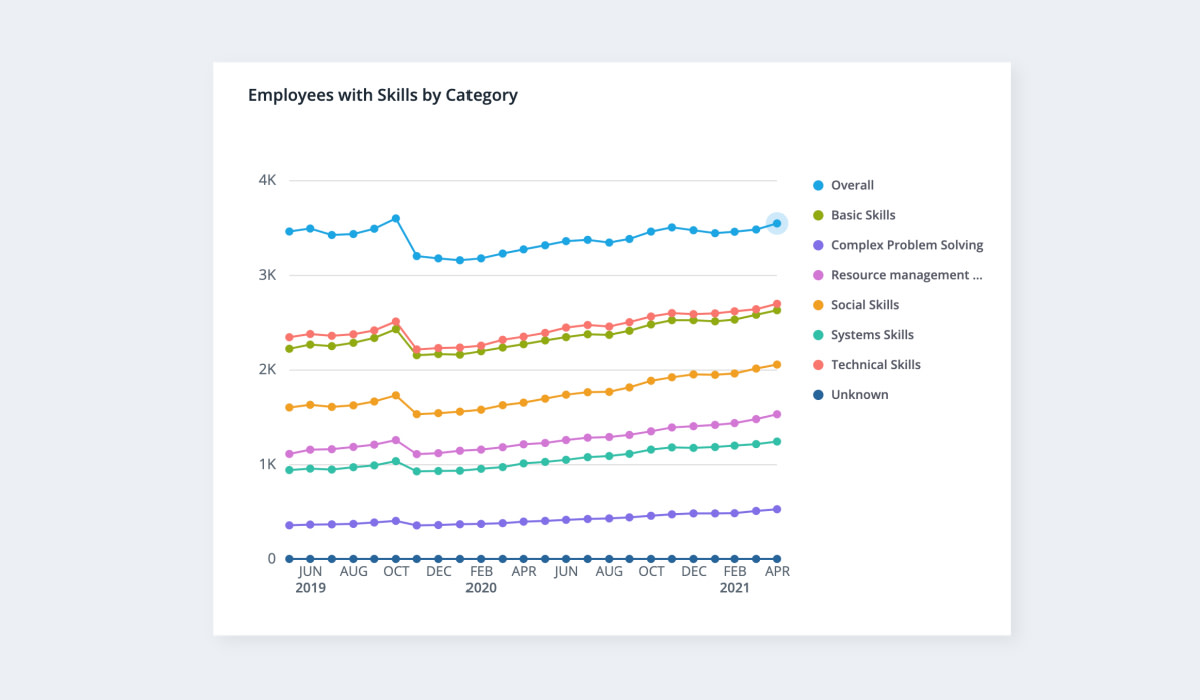

While the obvious solution is to move towards skills-based hiring, few companies are really exploring this arena to its full potential. College may be one-size fits all, but it is sometimes the only option people know of, because employers don’t really know how to find people they need. To bridge the gap, many companies are focusing more on partnering with universities to develop internship programs that will help develop both career networks and the hands-on skills that can’t be learned through coursework. Others are using technology solutions like Visier to show them which skills they have in their organization and which are lacking.

Because the job market fluctuates, knowing which roles are in high demand provides valuable insight to employers. Visier partnered with Emsi Burning Glass to pull information from real labor databases to provide a list of what kinds of skills people who have a specific job are expected to have, how rare that job is in that market, and what a competitive salary would be in that range.

Read this Visier survey to learn about the need for further investment in employee reskilling and upskilling.

Finding crucial job skills

Kevin MacDuff, Solution Management Director at Visier, explains that access to data will help leaders easily find, for example, everyone at their company who knows both accounting and Python. It will tell them how prevalent certain skills are within the organization and at what level of proficiency, so a finance director could find out if those accounting skills are at the level the company needed, and if not, whether it made business sense for the company to help employees develop those skills by funding job training.

A people analytics solution like Visier can help locate which skills are already present in your organization.

This is an advantage for employees as well. Many people find this less of a gamble than going deeply into debt to get a degree in a field that may not have jobs available in four years. Kevin says, “Pursuing a certification within the chosen field that you’re working in at the moment tends to be a bit easier.”

Kevin also says that mentorship programs often hit the job training sweet spot between hands-on experiential learning and theoretical learning. Third party programs, such as Degreed, do this well. “That’s the nice trifecta around having an internal talent marketplace that’s tied in with your learning platform: It’s the combo of courses plus gig opportunities plus letting managers offer up extra work that they’ve got that isn’t quite filled by skills on their team.”

Education may not be the same as it was in the early 20th century, but then again, what is? To prepare for the jobs of the future, we may need more than the job training systems of the past.

Further reading on job training and skills:

5 Learning and Development Questions You Can’t Answer Without Analytics

Is Job Skills Training a Valuable Perk? Hourly Workers Say Yes

Interested in learning more about Visier? Get in touch with us for a demo!