The Economic & Human Cost of Extreme Heat: Thousands of Deaths, Billions of Dollars

Unchecked, the climate crisis will cause catastrophe with workers dying and financial disaster. A number of recent reports lay out the impending meltdown.

This article was originally published in October 2021 and was updated in August 2023.

The first tropical storm warning ever for Southern California. Catastrophic wildfires and choking smoke clouds. Intense, sustained heat waves of temperatures over 100 degrees Celsius. Sounds like a disaster movie plot, but all these climate-related events happened inside of one week this summer, in 2023, claiming hundreds of lives and causing billions in damages.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) reports, "In 2023 (as of August 8), there have been 15 confirmed weather/climate disaster events with losses exceeding $1 billion each to affect the United States. These events included 1 flooding event, 13 severe storm events, and 1 winter storm event. Overall, these events resulted in the deaths of 113 people and had significant economic effects on the areas impacted."

July 2023 was the hottest month on record in 174 years.

The 2023 release of the U.N.'s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report asserted that humans are, in fact, the driving force of climate change, and detailed the catastrophic, looming deadline of early 2030s to keep the planet's temperature from rising above the 1.5 degrees Celsius threshold. Surpassing that number brings severe climate disasters that humans will not be able to adapt to—heat waves, drought, famine, and the spread of disease. And more billions of dollars in loss.

“The impacts of climate change are being felt in every U.S. state, territory, community, and sector. People are in harm’s way, infrastructure is increasingly outdated and in many places not designed for the new environmental realities,” Rick Spinrad, Under Secretary of Commerce for Oceans and Atmosphere & NOAA Administrator said in response to the 2021 UN climate report. ”Extreme weather events continue to occur one after another.” And they have in the two years since then.

These recent weather catastrophes are not a coincidence. They are a direct result of human inaction to curb greenhouse emissions. And many workers, especially those whose jobs are primarily outdoors, are bearing the brunt of climate change—both physically and financially.

Extreme weather’s effect on economy, jobs, workforce

Two studies suggest in the years ahead, that the climate crisis will have dangerous and deadly consequences on the U.S. workforce resulting in a costly impact on the overall economy.

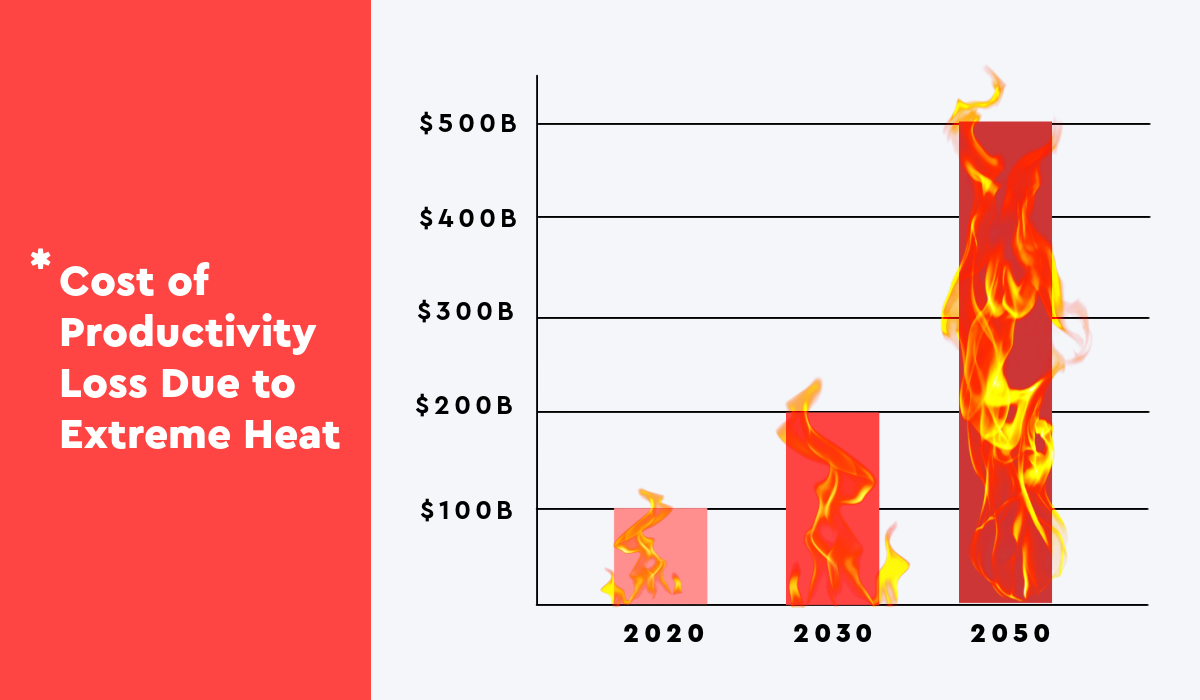

A report titled Extreme Heat: The Economic and Social Consequences for the United States published by the Atlantic Council’s Adrienne Arsht-Rockefeller Foundation Resilience Center found, “without meaningful action to reduce emissions and/or adapt to extreme heat, labor productivity losses could double to nearly $200 billion by 2030 and reach $500 billion by 2050.”

Yep. Billion.

*Without meaningful action to reduce emissions and/or adapt to extreme heat, per Extreme Heat: The Economic and Social Consequences for the United States

The report detailed the effects that extreme heat would have across several key categories—productivity, health, and socioeconomics.

Extreme heat is known to cause a decrease in labor productivity as a result of increased breaks and slower work. Heat can also increase the likelihood of mechanical failures causing machinery to overheat including computers or delivery trucks. Heat causes an increase in infrastructure failures (think runways becoming unusable in high temperatures) and causes absenteeism due to heat-related illness. A decrease in productivity can also be seen in agricultural/crop loss due to heat stress.

The health impacts of high heat can’t be overstated. The report predicts extreme heat will cause increased mortality rates and even premature death. Heat will cause occupational injuries (including heat-related illness and accidental injury). It causes morbidity from acute heat-related illness and exacerbation of chronic illness. There’s also the issue of soaring healthcare costs.

“Extreme heat is already a leading cause of mortality in the United States,” the report details, “but without adaptation, deaths could increase more than sixfold.”

source: atlanticcouncil.org

Under baseline climate and current demographic conditions, more than 8,500 deaths would be expected in a typical year as a consequence of daily average temperatures above 90°F, concentrated in the country’s hottest areas, says the report. “This is projected to increase more than sixfold to 59,000 by 2050, with increases projected to be concentrated in already hot areas in southwestern Arizona, Southern California, and southwest Texas, as well as becoming more widespread.”

In other words: Workers are dying of heat.

Heat-related deaths are on the rise

A recent study published by a research team made up of epidemiologists and climate scientists found that more than one-third of heat-related deaths are now caused by global warming. The National Weather Service cites extreme heat as the number one weather-related killer in the United States. On average, 702 heat-related deaths occur each year and experts warn this number will only continue to rise.

Construction and agricultural workers whose jobs are concentrated outdoors will suffer the most, experiencing significant impacts of rising temperatures. These workers also tend to be working-class and lower on the socio-economic scale.

A report released by the Union of Concerned Scientists in August also raises the alarm on the effects of extreme heat on workers:

“Each summer, the roughly 32 million outdoor workers across the United States—from construction workers to farmworkers to emergency responders—regularly face a brutal choice: risk their health by enduring dangerous exposure to heat or risk their jobs by staying home.”

Titled, Too Hot to Work, the report argues that urgent action is needed to reduce emissions, advance clean electricity, and invest in zero-emission vehicles.

If no action is taken to reduce emissions, the report says hot weather could cost outdoor workers a collective loss of $55.4 billion in earnings, each year, by 2050.

Outdoor workers extremely vulnerable

A farm worker on a turnip farm in Delano, California, 2020 (photo courtesy of UFW)

One such population that is highly vulnerable is farm workers, many of whom are undocumented, they spend their days outside in fields unprotected and uniquely vulnerable to heat-related injury and death. Elizabeth Strater, Director of Strategic Campaigns for the United Farm Workers, an advocacy group originally founded in 1962 by Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta, says millions of agricultural workers are at risk each and every day: “Eighty percent of the food we eat in the U.S. is grown here domestically. There are people right now—today, tomorrow—that are going to go out and work in the heat to produce the food that feeds this country,” she said in an interview with Visier. “And we need to understand that when people are working without protection, some will die doing that work.”

“For decades we’ve known that extreme heat is a deadly risk to farm workers,” Strater adds. “Heat kills farm workers every year.” When these workers are paid based on how much they pick, rather than an hourly wage, it creates a dangerous incentive to ignore signs of heat distress and push through and work even when the conditions are unsafe.

Farm workers in the United States are disproportionately vulnerable to the harsh effects of weather exposure. They are responsible for picking and processing 80% of the food eaten in the U.S. (photo courtesy UFW)

“It’s less money for them if they slow down, take breaks, and stay adequately hydrated,” Strater notes. “They need holistic protections while at work—cool water, shade, and rest rights that don’t cost them money.”

Strater and the United Farm Workers say more education is needed for both the employers and the farm workers to recognize when heat stroke and exhaustion are taking hold. They also say federal legislation and safety standards are urgently needed to protect vulnerable workers from extreme heat.

“What will it take to keep workers from dying needless deaths? We don’t have time to waste. We are tired of mourning the deaths of people who gave their lives to put food on our table,” Strater says.

New federal protections unveiled for outdoor and indoor workers alike—but will they work?

Labor advocacy organizations like the United Farm Workers are upset that there has never been a federal heat standard protecting workers in the United States. They have advocated for years to get federal protections in place, and although a handful of states have implemented heat regulations, federal protections have never been granted.

US President Biden announced a plan in 2021 to try to change that. Recognizing the impact of heat-related dangers on workers, President Biden says he’s committed to getting federal heat protections for workers in place.

“Heat is a growing workplace hazard, with the climate crisis making extreme heat more frequent and severe. Workers in agriculture and construction are often at highest risk, but the problem affects all workers exposed to heat, including indoor workers without climate-controlled environments.” A statement from the White House read.

Construction workers represent another heat-vulnerable group, although extreme heat can also adversely affect indoor workers when air conditioning is scarce due to resources or the location being one where overheating has not historically been a hazard (the Pacific Northwest, for instance)

Under the new plan, The Department of Labor’s Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) will develop workplace heat standards, increase enforcement of existing standards, develop a National Emphasis Program (NEP) on heat inspections targeting high-risk industries, and form a heat work group to better understand the challenges in protecting workers from heat hazards.

But OSHA’s record of protecting workers from heat-related illness and death has been criticized by an investigation conducted by NPR and Columbia Journalism Investigations. Their investigation revealed that at least 384 workers died from environmental heat exposure in the last decade, but they also say this number is likely an undercount: “OSHA’s record-keeping on heat fatalities is so poor that there’s no way to know exactly how many workers have died from heat.”

The investigation accused OSHA of failing to protect workers by not adopting a national heat standard strategy and refusing to regulate companies whose workers have died on the job. The report details some of these life-and-death working conditions:

“For at least a dozen companies, it wasn’t the first time their workers succumbed to heat. One worker collapsed and died after repeatedly complaining about the heat; another died after hauling 20 tons of trash for nearly 10 hours. In some instances, employees died after not having ample water and scheduled shade breaks. Many died within their first week on the job.”

With the White House’s new commitment to create a federal heat standard to protect workers, OSHA will have another chance to improve its regulatory efforts and enforce new laws both protecting workers and penalizing businesses that refuse to comply.

In July 2023 that President Biden asked the Department of Labor (DOL) to issue the first-ever Hazard Alert for heat which provides for the DOL to ramp up enforcement to protect workers from extreme heat. Scheduled for late 2023, the White House also announced a gathering of state, local, Tribal, and Territorial leaders—who are managing the lived impacts of climate change every day—for a White House Summit on Building Climate Resilient Communities.

Climate change is a DEI issue

The Columbia/NPR investigation found that workers of color are dying at higher rates than white workers.

“Workers of color have borne the brunt: Since 2010, Hispanics have accounted for a third of all heat fatalities, yet they represent a fraction—17%—of the U.S. workforce. Health and safety experts attribute this unequal toll to Hispanics’ overrepresentation in industries vulnerable to dangerous heat, such as construction and agriculture.”

These losses will disproportionately affect Black and Latino workers who make up more than 40 percent of the outdoor workforce according to the 2018 US Census.

Black/African American outdoor workers could risk annual earnings of an estimated $5.2-$7.5 billion and Latino workers could risk collective earnings of $11.2- $16.1 billion if there is slow to no action to reduce our emissions.

“Differences in heat exposure between outdoor workers and the rest of the population deepen existing social, economic, and health inequalities,” according to the Too Hot to Work report. Because Black and Hispanic workers are disproportionately represented in work that takes place primarily outside, earnings losses for outdoor workers “due to climate change could exacerbate inequities in health outcomes, poverty rates, and economic mobility, all of which result from centuries of systemic racism.”

Service workers need air conditioning

The Too Hot to Work report goes on to say that the industry most affected by extreme weather is the service industry. Overall losses will have the biggest impact in hospitality, transportation, education, and retail industries due to a lack of access to air conditioning exposing workers to dangerously high temperatures.

Climate change has a significant impact on productivity, health, and well-being. When it’s too hot to work, productivity wanes and heat-related sick-leave increases. A workforce dependent on air conditioning to keep them safe and high-functioning risks failure if the a/c can’t handle the heat or worse still, air conditioning isn’t available.

So how can employers mitigate and protect workers from heat-related events?

Experts say reducing physical labor during peak heat periods, increasing breaks to stave off heat exhaustion and heat-related injury or illness, make air-conditioning available where possible, provide easy and free access to water, and provide adequate training to managers about heat-related risks.

But no amount of workplace safety will have a greater impact than a collective global commitment to reduce greenhouse emissions. So rather than burdening a vulnerable workforce and risking an economic catastrophe, climate experts are urging action from governments and businesses alike to take responsibility to cut emissions, immediately.