A Moneyball Pioneer On Why Baseball Data Has Feelings

Ari Kaplan is widely considered to be one of the pioneers of sabermetrics. The moneyball pioneer breaks down the importance of using data.

In this new profile series, we sit down with interesting people and ask them to share the various ways their data-driven approach has served them in their life and career. Be sure to also check out the profiles on Kristi Zuhlke, Mert Iseri, and Alex White.

Baseball is a numbers game, but Ari Kaplan is invested in more than the ones on the scoreboard.

He is the co-founder of Scoutables (formerly AriBall) and widely considered to be one of the pioneers of sabermetrics, which is the practice of using in-game activity data and analytics to improve baseball game day strategy and player selection and management.

Moneyball–a 2003 novel by Michael Lewis turned into a 2011 blockbuster film of the same name–brought sabermetrics beyond the baseball diamond, and many business leaders have been applying the discipline to their own practices ever since.

“The biggest challenge is injuries. When you’re paying a player millions of dollars a year and they suddenly can’t play, their value goes down to zero.”

Knowing when to rest your players is a common concern in the world of baseball. And while what’s happening on the field may seem wildly different from what occurs in the workplace, the reality is that people are at the heart of both.

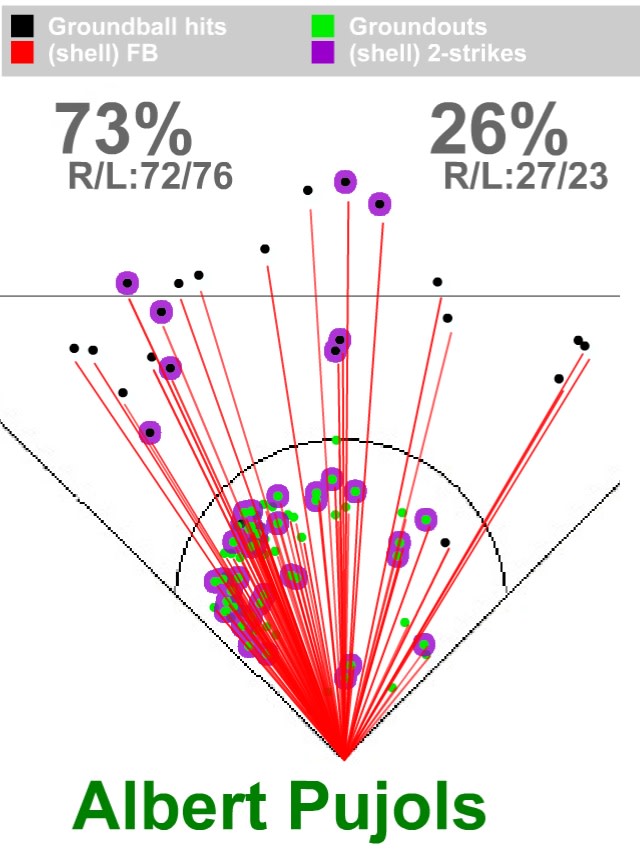

Kaplan has said, “These are humans, not computers playing. And humans often have subtle and repeatable habits that can be taken advantage of.”

He pays particular attention to this behavioral science involved in the game, believing that it’s a crucial piece that shouldn’t be forgotten when analyzing player performance and strategy.

“Things like player fatigue, their emotional state when they’re playing, and high pressure situations are all very important factors. In some cases you can quantify the impact of these and in some you can’t,” he says.

His way of handling “data with feelings” enables him to personally coach players to improve their game using fact-based evidence. Over the years, he’s been lucky enough to work with many MLB heavy hitters, like Anthony Rizzo, Kerry Woods, and Pedro Martinez.

“My natural curiosity was the driver.”

Growing up, Kaplan was always interested in figuring out how the world worked. This led to an early fascination with data science. When most kids were learning long division, he was writing video games and operating systems. It was his brother who fueled his love of baseball – Kaplan even played while he was at CalTech.

And it was while he was an undergraduate student there that his big break came, but it wasn’t on the field. He delivered a research project showing how sabermetrics wasn’t truly descriptive of how players performed. His work led to the development of new baseball statistics and formulas, and a chance at the majors: CalTech board trustee Eli S. Jacobs was so intrigued with Kaplan’s thesis that he offered him a job with a team he happened to own – the Baltimore Orioles.

As a special consultant to the Orioles, he designed and implemented computer and statistics systems to provide instant insights on major and minor league baseball players. He fondly recalls his first day on the job in 1991:

“I came into the office and found the data center destroyed!” he laughs. “Offices of baseball teams are [usually] in the stadium, and the data center was underneath a concession stand. When the beer sprung a leak, it seeped through the floors and wiped out the computers and backup tapes. It ended up being a good opportunity to start writing their scouting software [though].”

Since then, he’s had a storied career creating and developing scouting and player development database systems from the ground up for teams such as the Chicago Cubs, San Diego Padres, Montreal Expos, and Houston Astros. Over the years, he’s also worked at Oracle and Nielsen, and consulted for numerous organizations such as the U.S. Department of Defense, Hallmark, and PriceWaterhouseCoopers.

He’s never lost his entrepreneurial spirit though. His research at CalTech led to a partnership with Fred Claire, then-general manager of the L.A. Dodgers. In 2009, they founded AriBall (now called Scoutables), which is a SaaS platform that uses risk models to forecast the risk of injury to players. The platform helps teams proactively avoid financial loss due to injury.

“If you know the first batter takes the first pitch over 90% of the time…coaches have actionable pieces of info that lets them know they can pull a first pitch strike.”

When Kaplan first worked in baseball analytics in the late-80s, there wasn’t much technology to speak of. Creating the first scouting technology was an important achievement because it enabled him to, for example, give instant information on a shortstop to a GM without having to look for it by hand or sort through hundreds of files.

Today, a wealth of data systems exist that his technology can pull from, including StatCast (which records everything happening on the field), player salary data, and biomechanical data on player heart rate, bat swing and more.

Just like in business, the competition for talent is fierce, and analytics technology enables team managers to quickly make data-driven decisions based on all these data points. The Baltimore Orioles have had the best record in the American league since 2011 and achieved this with a lower budget. This was in large part because analytics have shown managers the benefits in developing undervalued players on the team.

“Analytics is in a renaissance time right now.�”

When it comes to analytics on the field or in the boardroom, context is key. With most enterprises around the world looking to get into analytics, this is a lesson Kaplan hopes business leaders will take to heart. He also offers this advice:

“Whether its people or products, you need to know what is the context of the information and how you can take some real life action on it. Then you need to make it simple enough for others to understand.”

Kaplan is looking forward to the next wave of technology that could be hitting the field, which he believes is all about making data more accessible. He wants to see more self-serve analytics so non-data scientists can get insights with ease, machine learning that comes up with questions someone may not have thought to ask, and natural language processing that summarizes millions of player data points into plain English.

“It won’t be about watching a chart or looking at a spreadsheet anymore,” he says.

Photos have been used with permission of Ari Kaplan.