Counter Offers: Know When to Hold’em or Fold’em

HRBP's are approaching counter offers like a game of poker. How do you avoid losing top talent to a higher paycheck? Learn more.

How do you avoid losing top talent to a higher paycheck? How should your company react to counter offers? Is raising salaries the only solution?

Counter offers are a tricky business. For example: Marie, a sales director earning $120,000 per year, enters her manager’s office one day and announces that the firm down the street has offered her a position with a 10% salary increase.

In the mind of her manager, Marie’s work performance is above average and she has potential, according to a recent talent review. However, she has not had many opportunities to prove herself because her tenure has been relatively short. Also, she has a history of asking for more: within the past six months, she requested (and received) a 3% increase.

Should the manager counter-offer to keep Marie? Or will it be better in the long run to let her walk away now? Facing this complex decision, the manager immediately calls the HR business partner for support.

If you work in HR or have managed a team, it’s likely that you understand the dilemma presented by this type of scenario: Competition for talent is fierce, and when an employee leaves due to voluntary turnover, it typically costs 1.5 times that person’s annual base pay to fill the vacant position, according to the industry standard calculation. At the same time, giving raises when they are not warranted will lead to pointed questions from the executive team.

It is no wonder that managers and HR business partners are approaching counter offers the same way they would a high stakes game of poker. As Kenny Rogers would say: “You’ve got to know when to hold’em; Know when to fold’em.”

So when should you “hold’em” and provide a counter-offer or “fold’em” and let an employee walk away?

Often, this kind of situation is viewed as a game of chance based on gut feel, which can lead to costly mistakes: Intuition — a mental “shortcut” — is the result of two hardwired processes (pattern recognition and emotional tagging), which frequently lead to cognitive errors, according to psychologists. This causes even the best managers and HR professionals to make poor judgement calls.

Instead of accepting an intuition-based talent decision, consider taking an analytical approach: by accessing the employee’s detailed work records and performing comparisons against like employees and employee groups, you can make better decisions based on evidence.

Whenever you are faced with a counter-offer dilemma, use the steps below. They will help you dramatically increase your chances of making the right move to keep the right talent — at the right price.

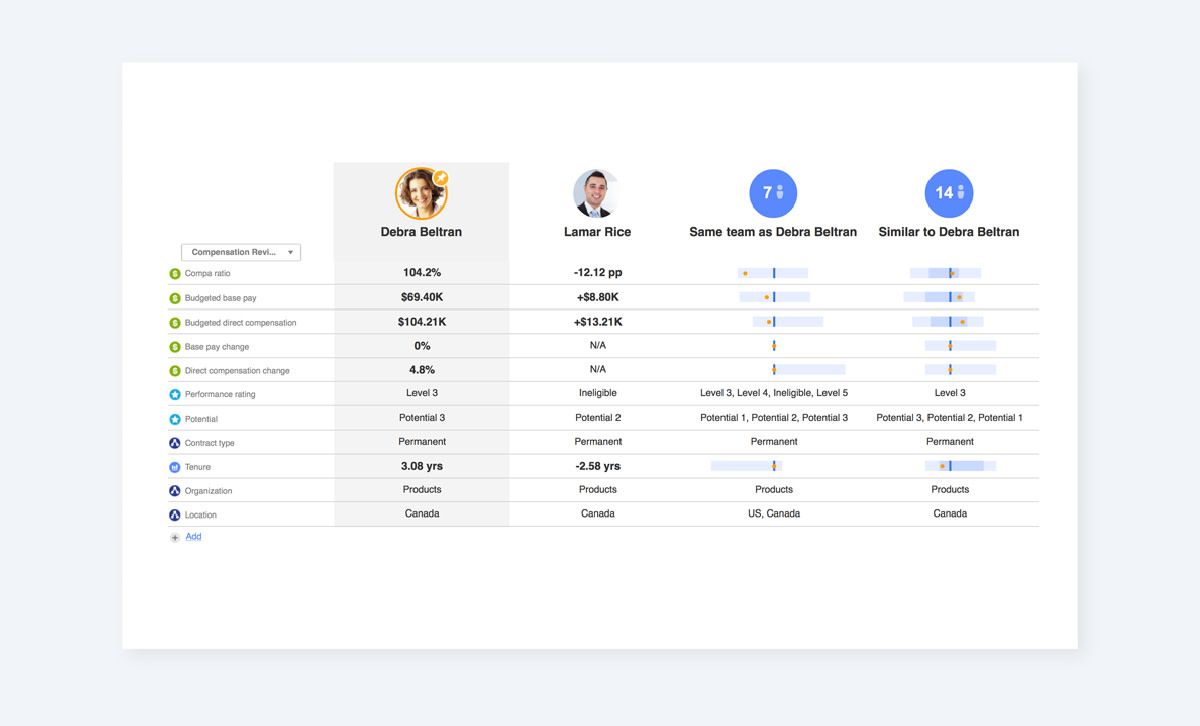

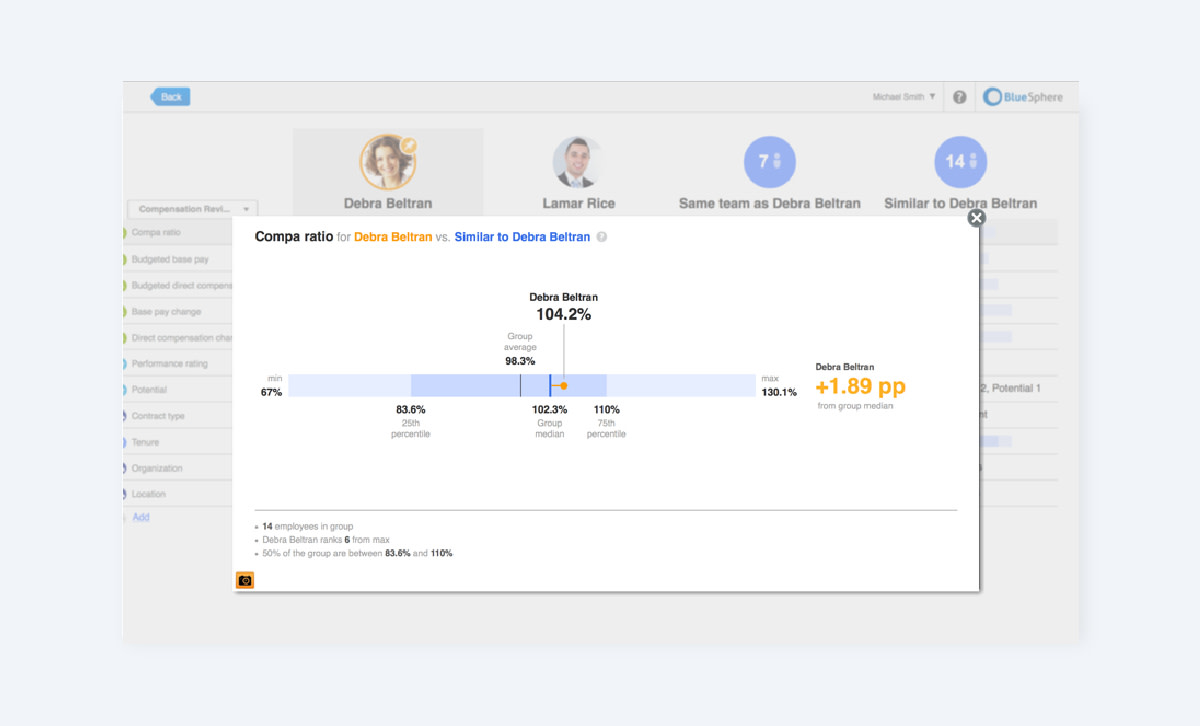

Step 1. Compare peer and employee group compensation levels

The first step is to compare the employee’s salary against the earnings of his or her peers and employee group, taking job performance into account. This will help you determine whether you are paying this person fairly within your own compensation framework.

To fully understand the situation, compare the person against:

Direct peers – The first and most relevant comparison is to the people who perform the same role, at the same level, and in a similar geography. By comparing the employee to these people you can establish a clear picture of whether or not the person’s situation is unique: Is she a higher performer than others? Is she rewarded fairly compared to these people?

His or her employee group – The individual may be above and below specific direct peers; however, it is also important to understand whether she is above or below the median for her peers when they are considered as a group. For example, if she is below the median on pay and above the median on performance for the group, then the data suggests she could be worth the additional salary.

Similar employees across the business – Finally, compare the individual to people who are similar to the employee but maybe work in different geographies or different functions. This comparison helps you determine how well she is being compensated within her existing pay band. Where does she sit in the distribution? Are there many examples of people who are at the higher end of the pay band that would set a precedence for a compensation increase?

If, after analyzing the above areas, you determine that your organization is not paying the individual fairly, your next course of action is clear: you need to counter-offer.

However, if you are indeed paying the individual fairly relative to other people within the organization, then the next phase of questions come into play.

Step 2. Assess the individual’s current and potential value

A key role of the HR Business Partner is to help the business understand the current and future worth of their people. Once you have ruled out the pay fairness question, you need to ask: “What is it worth to the company to keep the employee?” Here are the key attributes to consider:

Performance potential – According to McKinsey’s War for Talent study, top talent employees generate 40% more productivity in operational roles, 49% more profit in general management roles, and 67% more revenue in sales roles when compared to an average performer. Having top performers leave a team will significantly impact the team’s ability to reach business goals, therefore it is important to determine whether or not the individual has the potential to be a top performer within the organization by looking at their results overtime and their ratings in relation to future value / potential in the organization.

Tenure and time in position – Organizations and markets are complex — it is insufficient for an employee to simply know the mechanics of his or her job function. Success also requires people to build, maintain and leverage relationships — inside and outside of the organization — to get results. Hence an employee’s length of service and the specific amount of time they have been in a role are key components in determining their current and future value to the organization. A short time frame and high performance are positive, but mean the employee has not been tested over a sufficient period of time. Long service and steady or declining performance may indicate a career plateau or the need for change.

Potential future value – This looks at the employee’s capacity to progress to a more complex role in the organization. A counter-offer to try to keep the individual may move her beyond her pay band for her current position. However, it may still be a wise investment to keep her for a potential future role as external hires make 18% more than internal promotes in the same job.

While the above areas are crucial to examine in every counter-offer situation, the specific attributes of each employee and how these relate to overall business goals will be different. It is important to review these core components and consider other aspects of the employee’s situation, such as their promotion history, to determine whether this is a high value individual who is worth a counter-offer.

Step 3. Determine the consequences of letting the employee walk

At this stage, the evidence may indicate that a counter-offer is not a good course of action: perhaps the employee is already at or above the median for pay compared to her peers, and has average performance potential.

But before making a final decision, it is important to consider what it will take to replace the employee — whether you are leaning towards a counter-offer or not. Workforce analytics — that look at and deliver insights based on data from all your HR systems, not just your HRIS — can help you look at several attributes at once to quickly determine the following:

How long did it take to fill her position in the past?

How many junior people are ready to move in to her role?

What is the likely ramp-up time for someone new into this role?

If the employee is relatively easy to replace, then the impacts of letting her walk are not as great. However, if you will be without an employee for a long time and this will impact business results, then it may be more business savvy to make the counter-offer and work on a backup plan.

Step 4. Bring it all together

There is never one way to position a counter-offer. If all signs — compensation, performance, future value, replacement costs — indicate that you should counter-offer, you need to put forward the best strategy to get the result you want.

For example, if a top performer is due for a promotion, non-monetary factors will play a bigger role in keeping her. For someone seeking a 10% increase, but who has not yet proven her value, you could offer a 5% increase this year, or a 10% next year based on achievement of targets. Some organizations offer retention bonuses over a two-year time frame to compensate for delayed career progression or similar situation. All of these are viable options and determining the right one is where HR plays a critical role in driving business results.

If you have determined that you want to keep the person, but do not have the budget to meet the requested raise amount, you can consider a range of options, including performance-based incentives, agreeing to a review compensation within a certain timeframe, or provide a range of development opportunities.

Whatever you chose to offer, it is a wise course of action to add up all the tangible and intangible compensation items — like health benefits — so you can truly differentiate the overall package your company offers that the new company may not provide.

If you have followed the steps above, you will have all the data you need to help you find and present an effective strategy.

Make Intuition Part of the Scientific Process

It’s only human to have a gut reaction when an employee says they have a better offer somewhere else, and this reaction may be false. But as academic Tom Davenport writes in this HBR blog post on big data and the role of intuition, it’s not about completely ignoring your gut, but viewing it as part of a bigger process:

“….a hypothesis is an intuition about what’s going on in the data you have about the world. The difference with analytics, of course, is that you don’t stop with the intuition — you test the hypothesis to learn whether your intuition is correct.”

So, when you get a sudden request for a counter-offer, you will likely start with an assessment of the situation based on your intuitive abilities to read other people based on past experiences (whether you consciously know it or not). But you also need to act like a scientist: let your initial gut reaction be a starting point, but then ask a lot of questions and put your theories to the test by gathering the evidence.

This way you won’t kind of know when to “hold’em” — you will know — and will be in the strongest position to have the game play out the way you want.